Fuse – Sensory Augmentation for Pilots

Built a vibrotactile vest that provides spatial feedback to airplane pilots.

Introduction

The ocean of possible human sensory experiences is vast: the sound of a symphony orchestra playing Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, the touch of cool grass between your toes, and the warmth of a good meal after a long, cold day.

For all the richness we experience, it’s funny to remember that everything we are lies enclosed in a dark, rigid vault. Our windows to the outside world take the form of rotating fluid canals, vibrating drums, tangled circuits excited by photons and molecules, and one of the most computationally advanced fabrics known to nature.

Our senses feel very different, and the sensors we use to detect different physical phenomena reflect that — our eyes are very different from our tongues, and our noses are different from our ears. Yet the way this information is processed and communicated in our brain is of the same currency — electrochemical signaling in the form of the well-loved action potential. All your brain has access to are these signals. This fact leads us to an interesting thought experiment: if the brain uses the same language to describe sound, sight, smell, taste, and touch, could it also be used to describe wholly different kinds of sensations?

In the absence of observers, reality doesn’t inherently look, sound, smell, taste, or feel a certain way. Our perception of it is purely a result of the sensors we have, which is why different animals experience reality so differently. And while the human experience is vast, we occupy an unbelievably thin slice of reality.

Dr. David Eagleman, an advisor for this project, compares the human sensorium to Mr. Potato Head. According to his theory, the brain is a general computing device that takes information in from its sensors (eyes, ears, etc.) and just figures out what to do with it, in much the same way a child can put Mr. Potato Head’s limbs anywhere and he can still theoretically function (despite taking on a bizarre and horrifying existence). Not only can the brain adeptly decipher new inputs, but it can dynamically allocate resources: take away one’s vision and the auditory cortex will expand into the now unused territory of the visual cortex, heightening one’s sense of hearing. Neural plasticity, or the ability of the brain to restructure itself, underlies this seemingly magical phenomenon.

This ability of our brains to adapt to what information they receive leads us to an exciting idea: sensory augmentation. There’s two kinds of ways we can augment our senses: the first is sensory substitution, or using one sensor to convey information normally collected by another – for example, using touch to communicate auditory information. This is often most useful for someone missing a sense — i.e. a blind or deaf person. The second kind of augmentation we can think of is adding new senses entirely. There are plenty of signals too small, too fast, or invisible to our naked eyes that we don’t directly experience. Additionally, there is more abstract information that we can’t directly sense — what would it look like to directly feel the health of an economy or the wellbeing of a community? Sensory addition explores fundamentally expanding our sensory toolkit.

Dr. Eagleman has demonstrated sensory substitution with his current company, Neosensory. Their flagship product is a wristband with four small vibration motors built into the strap. These motors vibrate according to the acoustic landscape around them, transducing sound into vibration via a frequency-modulation algorithm. The device listens to a small sound snippet, determines the frequency most prominent in that snippet, and vibrates at a point along the wristband corresponding to that frequency. After some time training, what results is nothing short of science fiction – augmented hearing for those with significant hearing loss. If the brain really is a general computing device with little preference for any particular peripheral, why not exploit our most underutilized peripheral — the skin — for information transfer?

This was the inspiration for Fuse.

Problem Selection

This summer, we wanted to demonstrate the limits and opportunities of sensory augmentation. Some criteria for choosing an application space/problem were:

-

We wanted a problem space where information transfer is cumbersome.

-

We wanted to show that sensory augmentation could be a solution via a rigorous set of experiments.

-

The problem involves complex spatiotemporally varying data that would allow us to probe at the upper limits of information throughput.

-

We loved the new Top Gun.

Based on these criteria, we decided on aviation. For pilots, acute spatial and situational awareness can often mean the difference between life and death. Between 2000 and 2009, for example, a condition called spatial disorientation – which occurs when a pilot cannot accurately determine their orientation – accounted for 26% of accident fatalities in the U.S. Air Force.

Pilots, particularly in military and rescue operations, are constantly inundated with complex information. Given that this information is presented almost exclusively visually through dozens of small gauges, pilot awareness is bandwidth-limited. Consequently, a pilot’s attention becomes extremely fragmented — check altitude, look outside, check airspeed, look outside, contact ATC, check heading, look outside, etc.

Proposed Solution

Good communication is multimodal. We use language to discretize and communicate the amorphous mess of thoughts in our minds. It allows us to transmit critical information to others at the speed of sound. Yet we know communication is also visual. Think about the importance of body language when conversing. Imagine trying to communicate the same nuanced emotions without someone seeing your facial expression, hand motion, or body positioning. This new sensory dimension to conversing adds a deep richness and transfers more information than a single modality alone. Why stop there?

In high-pressure situations, a pilot’s sense of hearing is the first to go. For example, airplanes are equipped with verbal alarms that say things like “too low, terrain” or “pull up,” but when the metaphorical piece of bird poop hits the turbofan (iykyk), pilots are known to filter them out.

By creating a new language whose words are vibration patterns on the skin, we believed we could give pilots a much more direct, continuous experience of critical information. By encoding information through different channels (visual as well as haptic) we can perform a sort of information multiplexing so as not to overload any individual sense.

Encoding Scheme

Making sense of information from the outside world requires a currency exchange. Somehow, we must convert a physical phenomenon like the vibration of air molecules to electrochemical signals. This is a process we take for granted every day; in fact, this might be the first time you’ve ever actively thought about it.

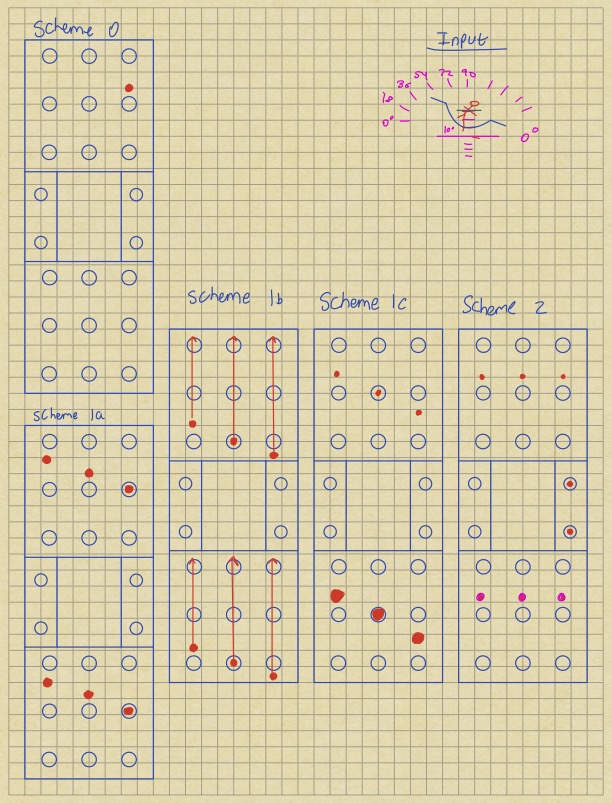

When applied to generating vibration patterns on the skin, we call this currency exchange an encoding scheme. We spent a lot of time designing possible encoding schemes, ranging from one as simple as having four motors on the chest in an up, down, left, right configuration to communicate roll and pitch, to a 26 motor arrangement that would allow for vibration sweeps along the skin. Two important considerations we had for the scheme were:

-

Maximize information throughput (the amount of information, usually measured in bits, communicated to the pilot via the vest per unit time).

-

Maximize intuitiveness. We hypothesized that if there were a clear isomorphism between the scheme and our intuitive understanding of the action being performed, that it would be learned faster (e.g. if we wanted to communicate roll angle intuitively, rolling to the right should intuitively produce vibration on the pilot’s right side, while rolling to the left should stimulate the left).

Below is a list of encoding schemes we thought of, along with diagrams and explanations. When we created this list, we assumed we’d have 9 motors on the front, 9 on the back, and 2 on each shoulder strap. The real-life constraints of DIY hardware projects soon caught up with us, however, and we made do with 6 motors in total – one on each shoulder, one on the chest and back, and one on either side of the stomach.

Scheme 0

One point of vibration on the chest to represent only roll and pitch. The horizontal and vertical position of the point is dictated by roll and pitch angle, respectively. In this example, since we’re rolled to the right and pitched up, the point is located near the top right of the vest.

Scheme 1a

A line on the chest and back that mirrors the artificial horizon, or attitude indicator. In the above example, we’re banked right about 36° and pitched up 10°. The artificial horizon would give something similar to the example in the top right of the below picture. This scheme would therefore produce a line with negative slope, mirroring the light orange line on the indicator. The vertical displacement of this line from the vest’s centerline represents pitch angle.

Scheme 1b

Very similar to 1a, with a line representing roll angle. Here, however, pitch angle is represented differently – instead of vertical displacement from the centerline, we use upward or downward sweeps (represented by the red arrows). The velocity of the sweep represents pitch angle.

Scheme 1c

In this scheme, we still use a line to represent roll angle. For pitch, we use differing intensities between the back and chest. If we’re pitched up, the vibration line on the back will have a higher intensity than that on the front, and vice versa if we’re pitched down.

Scheme 2

Here, we no longer represent roll through an angled line. It is represented by vibration on the shoulder corresponding to the roll direction. Pitch is represented by the vertical displacement of a horizontal vibration line from the vest’s centerline.

Testing Approach

A friend gave us critical advice early on, which was “rush to fly.” By this, he meant that iteration and periodic feedback were far more important than perfection – pilots would be more than willing to help. This led to perhaps the most important personal and project-related realization of the summer – people are often willing and excited to help; all you need to do is persistently ask.

We kicked off the project in early July with a discovery flight, which is a 2-hour flight lesson given to novices by a certified flight instructor (CFI). We flew with Advantage Aviation in Palo Alto, and our CFI was incredibly open to helping us learn what we needed to know for the project. We began with an hour of ground school, during which we learned about the flight characteristics of the Cessna 172 Skyhawk and the procedures for take-off, landing, and flight. We then got into the airplane, and our CFI walked us through a range of flight maneuvers, including steep 45-degree banks, stalls, slow/fast landings, and take-offs.

The Neosensory Buzz

After the discovery flight, we began building. Our first goal was to determine whether Neosensory’s Buzz wristband would be sufficiently intuitive and transfer the required amount of information.

Vest 1.0

In short, for the amount of information we wanted to convey, the Buzz seemed limited and, most importantly, unintuitive, so we decided to upgrade to a vest. The benefits of a vest not only include additional motors, but also a much more intuitive motor positioning. The materials we used were:

- This cooling vest

- These ERM (eccentric rotating mass) motors

- Velcro to mount the motors to the inside of the bed

- An Arduino Uno

We still needed a way to send this vest the flight information that would then translate into vibration. We began by using the roll and pitch values obtained from this IMU and got the full system working using an encoding scheme similar to scheme 2 (adapted for our 6-motor configuration). This was an important milestone, but one key element was missing – continuous feedback. Turning the IMU over in one’s hand allows one to experience its tilt angle through vibration, but it does not provide the type of feedback required to integrate those vibrations into a continuous internal map of orientation, as flying a plane would have. This led us to our most important breakthrough in the testing process – integration with Microsoft Flight Simulator.

Oshkosh, aka The Burning Man of Aviation

On July 27, we traveled to the small town of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, population 67,000. The occasion was the world’s biggest airshow, EAA AirVenture, population ~700,000. There was music, fireworks, and lots of Top Gun-style fighter jet demos. We were in heaven (despite heavy sunburning and a tent a touch too small for two).

We attended with a few goals in mind – to gain exposure to the countless types of planes and pilots who might benefit from Fuse, to assess state-of-the-art pilot assistance technologies, and to try out the vest with any pilot who’d be willing to give us a shot.

While we learned a ton throughout the week but were nearing the end of our time and had yet to test the vest in the air. We had somehow managed to get a vest strewn with metal and wires through TSA and AirVenture security (“I promise this will NOT explode, Mr. TSA Officer), but were going to come back without having donned it once. Things weren’t looking good.

When some people think of the word “Savior,” religious iconography comes to mind. For us, it came in the form of an old guy named Gary.

We met Gary on the second to last day of the airshow. He owned and flew a T-6 Texan, an old plane used during World War II. After some convincing (and manual labor on our part), Gary approved a flight and allowed Dhruv to hop in the back seat while wearing the vest over a baggy jumpsuit. We came away with a key finding: even through a thick shirt and a jumpsuit in a heavily vibrating plane, we could still feel the vest’s motor vibration patterns. Changing motors would have complicated our design, so we were thankful that we could get away with our cheap ERMs.

Prototype V1.0 x Microsoft Flight Simulator

The turning point of the summer came when we integrated the vest with the Microsoft Flight Simulator SDK. Previously, we had only an IMU to send data to the vest, which did not create an immersive testing experience. For the flight simulator integration, we wrote a script that sent all relevant flight parameters during a flight over a live serial connection to the Arduino.

Now it was much easier to try out various encoding schemes. The one we settled on was similar to scheme 2, with roll mapped to the shoulders and pitch mapped to the chest and back. We chose to use the stomach motors to communicate heading, which we represented via periodic vibration pulses on the right or left side. If North was between 0 and 180-degrees clockwise, the right stomach motor would pulse with an intensity corresponding to the magnitude of the angle between forward and North. If North was between 0 and 180-degrees counterclockwise (or 180 and 360 degrees clockwise), the left stomach motor would vibrate according to the same rule. We encoded turn rate through the frequency of the pulses – the greater the turn rate, the higher the frequency of the pulses. For example, if our heading was West and we were turning quickly towards North, we would feel rapid pulses on our right stomach, beginning at medium intensity and decreasing to zero intensity as we approached North.

More Testing and Results

We’re still developing tests for information throughput and learning rate. At the end of the summer, we performed two.

Test 1

Our first test was very basic and only involved the flight simulator. The pilot closed their eyes while the observer put the plane in an unusual attitude at an unsafe airspeed. The pilot was then asked to open his eyes and recover. After only a few trials of similar difficulty, we found that recovery times were reliably cut by about 40% (8 seconds to 5 seconds) compared to controls without the vest. While we want to better quantify the difficulty of the different initial conditions we put the pilots in (and test in a controlled but more realistic setting) these initial results were very promising.

Test 2

Our second test was more thrilling. This time, we flew in a real plane. Dhruv was in the pilot seat wearing the vest while a CFI at Advantage Aviation acted as safety pilot. The most informative test we performed during this flight was as follows. The instructor asked Dhruv to close his eyes. He then asked Dhruv to perform a turn with a specified end heading, all without his vision. Below is a video of Dhruv successfully performing a bank from West to East and leveling out. He had his eyes closed for the entire maneuver, with only the vest to convey roll, pitch, turn rate, and heading.

This turn was done with extreme accuracy (don’t worry, we aren’t biased at all). Incredibly, while roll and pitch are communicated quite intuitively, heading is a different story. Periodic pulses on the stomach are far more abstract than vibration in the direction of roll, for example. Yet, Dhruv not only ended the turn at the correct heading, but also maintained safe roll and pitch angles throughout, showing that all three information streams could be understood and integrated simultaneously.

In it, Dhruv performs a turn from West to East, then levels out, with his eyes closed the entire time. The “wow – oh my, oh my god” at the end of the video is a result of his surprise that it actually worked.

Open Questions

We have more questions than we did when we started, and that’s exciting. We hope to inspire the neuroscience and hacker communities to help us develop this technology and find answers.

- When does sensory augmentation exacerbate task saturation?

- How can we demonstrate that the user is not thinking about the information they’re receiving for decision making, but is instead using it subconsciously? In other words, how can we quantify and minimize the role conscious cognition plays in the sensory input to decision making pipeline?

- Is it better to encode an error signal or the raw value given by sensors? In other words, should a vest or other sensory augmentation device dictate to the user what action to take, or simply communicate the user’s current state and leave the decision making to them?

- What benefits/drawbacks does encoding information in higher dimensions/more abstractly yield? How much does “intuition” matter?

- Is it possible to develop a new language that uses other sensory channels in tandem with our auditory system so we may increase information throughput in day to day communication?

- How might we achieve entirely new qualia?

Answering these questions will fundamentally change the way we experience the world. It is an exciting time to be a budding neurotechnologist!

Future Work

This summer was merely the beginning of Fuse. We’re in contact with the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) to explore applications and testing opportunities in military aircraft. In the next few months, we’ll be conducting more concrete tests, designing more complex encoding schemes, and attempting to quantify important upper bounds on information transfer through the skin.

Conclusions

We believe there is great potential in sensory augmentation through the sense of touch. Our experiments at the end of the summer demonstrate not only pilot performance improvements with Fuse but an entirely new and wonderfully unexplored method of obtaining and interpreting information from the physical world.

While recreational pilots have been incredibly helpful to us for testing purposes, we believe this technology would be better suited to more dangerous or high-intensity applications where high throughput information transfer can make the difference between life and death. Within aviation, applications include search and rescue, military, and aerobatics.

One concern of ours was information overload and task saturation. Would a vibrating vest only add to the pilot’s cognitive load, outweighing the benefits it provides? Based on our tests thus far, the answer to this question is no, as after a little practice, the vest no longer feels out of place. In the same way you feel the clothes you’re wearing as you put them on, but the sensations are filtered out from conscious perception in a matter of seconds, the vest becomes less intrusive over time, despite being able to actively communicate information. This is very promising for future wearable sensory augmentation devices.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you. Let’s go expand the sensorium and human thought space with it.

– Dhruv and John

Acknowledgements

There are plenty of people without whom this work would have taken much, much longer to accomplish.

Firstly, we’d like to thank Quintin Frerichs and Fred Ersham for funding our project with a research grant. Quintin has been an excellent mentor and friend.

We’d like to thank Professor David Eagleman, who has worked tirelessly amid lots of uncertainty to push sensory augmentation forward through Neosensory. He helped us question our fundamental assumptions about design and spared us from pursuing many dead ends.

We’d also like to thank Deborah Kirkman and the Flight Safety Foundation for the advice and introductions they gave us as we navigated the unbelievably complicated field of aviation.

Finally to all the wily pilots who took us under their wings, we wish you blue skies ahead.

If you have questions or would like to collaborate with us in any capacity, please reach out to dhruv.sumathi@gmail.com.

Works cited

- Perrotta, M. V., Asgeirsdottir, T., & Eagleman, D. M. (2021). Deciphering sounds through patterns of vibration on the skin. Neuroscience, 458, 77–86.

- Gibb, R., Ercoline, B., & Scharff, L. (2011). Spatial disorientation: Decades of pilot fatalities. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 82(7), 717–724.