What If We Could Live Longer?

We Shouldn’t Be Here But We Are

You are the result of nearly 14 billion years of atoms bouncing around randomly and occasionally making larger, more ordered structures. The biological evolution that birthed you was a 3.5 billion year house of cards, a chaotic scrapbook of “whoops, that shouldn’t have worked” moments and flimsy miracles stacked so high the whole thing should have toppled over by now. You were the one lucky sperm that made it to an indifferent egg to make this entire human being, this computer they say is the most advanced we know of and if any other sperm had hit the same indifferent egg then you would just… not exist.

And then they tell you that if you’re lucky you’ll have 100 years to roam the forests and mountains and deserts and cities and beaches. 100 years to experience beauty, happiness, fulfillment, pain, sadness, and so on. You’ll find some pretty seashells, and you’ll lose some, but you’ll find more, and by the time you’re old you’ll have a nice little monument to your time as a collector on the sands. And then you’ll just leave them there – for the wind or the strangers to scatter – and you’ll wade into the ocean where you’ll spend the rest of eternity in darkness. And they say that’s good. It’s natural.

And we say, “that’s beautiful.”

We say it makes the seashells all the more pretty.

3.5 billion years of unimaginable luck to make you, this ridiculously unrepeatable symphony of neurons and hopes and dreams and quirks and bad jokes, and someday you’re supposed to shrug and say, “Cool, guess I’ll just dissolve into the void now”.

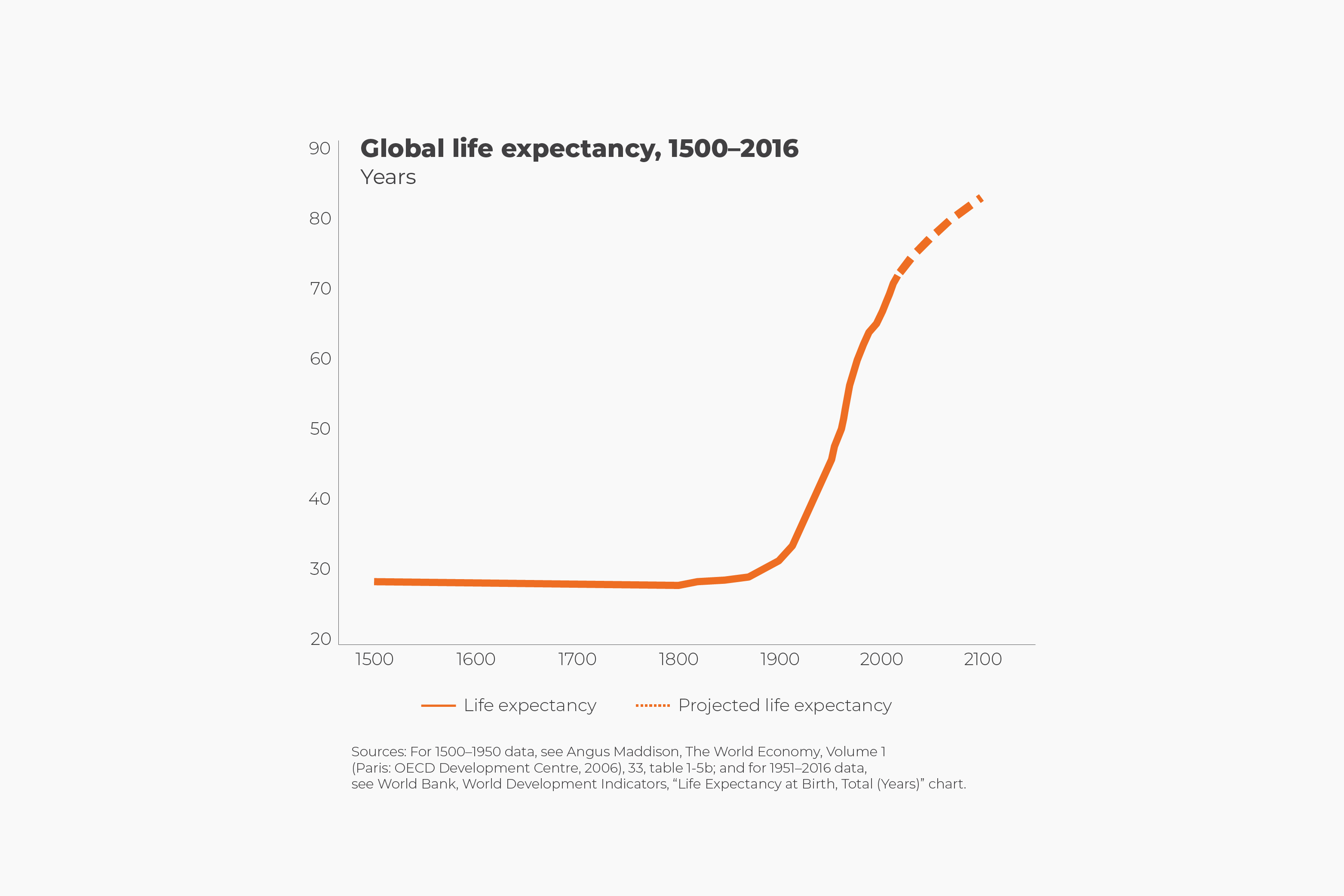

And we accept this because it’s “natural”? The farmer in medieval Europe sentenced to a pneumonia-induced death at the ripe age of 30 probably thought that his plight was “natural.” But society chose to say no, we disagree, and so we extended lifespans to the 70’s and most of us seem to be grateful for that. When are we supposed to say, “stop, I’ll take this much extra time but no more?”

We’ve baked death deep into our culture. We call it necessary, and many call it beautiful. But I believe we are so fully and wholeheartedly surrendered to it because that’s the only way to cope with the unbelievable tragedy of it all.

In Our Time

As we age, we normally contract diseases. Sometimes there are cures. Historically, aging has outpaced these cures – even the luckiest among us eventually die of old age. Soon, though, treatments may outpace aging—what some refer to as “lifetime escape velocity,” where each year of treatment advancement adds more than a year of potential lifespan. **It’s hard to say where this trend could stop, or if it will take our lifespans all the way to “as long as there are resources to exploit in the universe,” but there’s a lot of whitespace there. I believe much of humanity will reach lifetime escape velocity in this century.

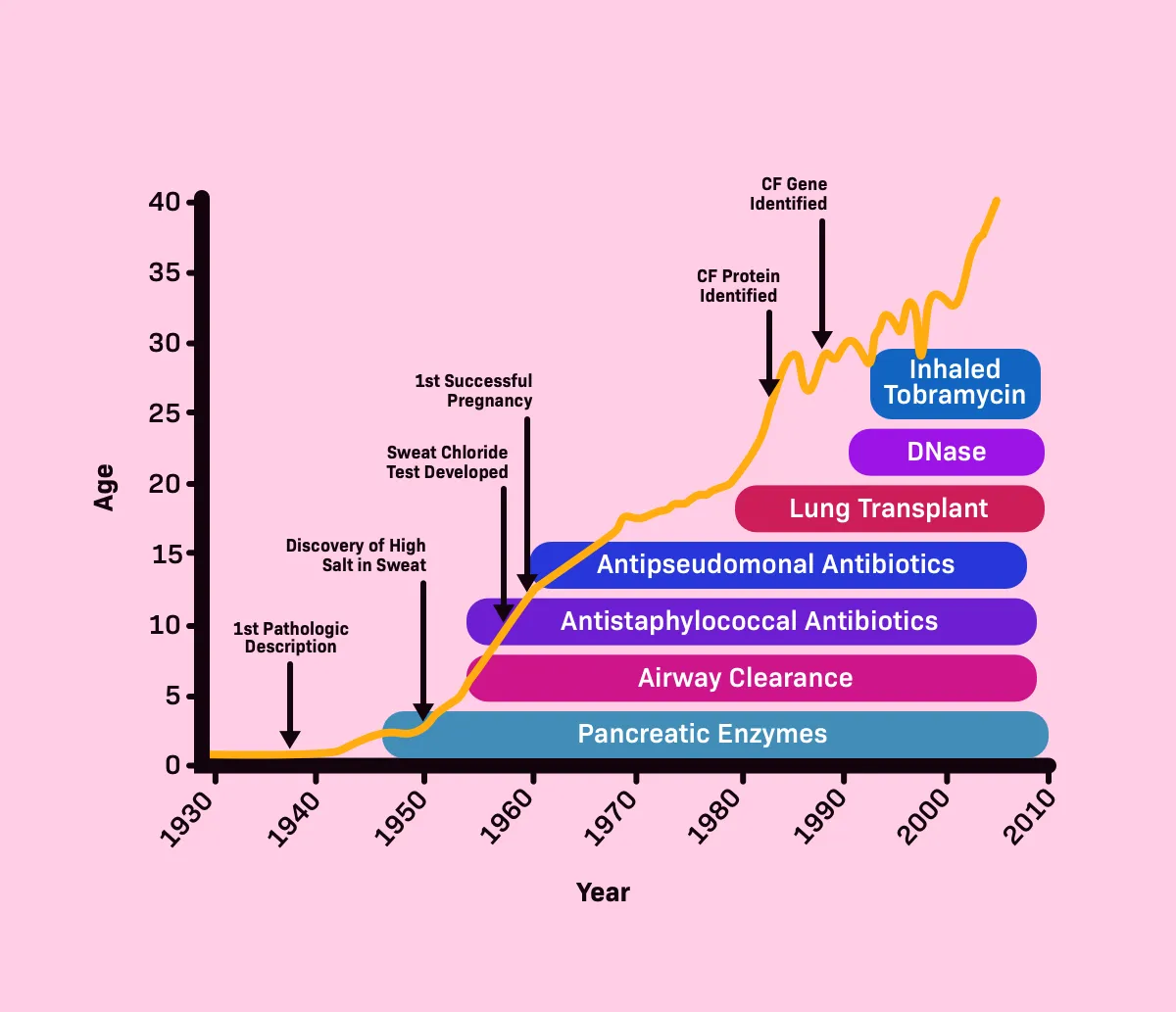

Consider cystic fibrosis as an example. This graph shows the median age of survival for cystic fibrosis patients over time, as new treatments were invented.

A child born in 1950 would barely survive beyond infancy, but incremental advancements have continuously extended survival. Imagine if medical progress outpaced disease progression dramatically; those born with seemingly insurmountable conditions could enjoy full, healthy lives.

Even if we discover a hard limit to lifespan, the cause is not lost – it’s a real possibility that some neurotechnologies will allow us to live on in some way, through a gradual transfer of cognition to computers like the kind described in this short story.

What if we could live for hundreds of years, or thousands, or longer? I think a few natural things would happen:

Individual and Collective Thoughtfulness

If in the default path we’re to live for a very, very long time, the stakes of our decisions would get higher. For one, I’d be much more careful crossing the street so as not to squander all of that potential being flattened by the local bus. And I think that caution would scale to society as a whole, because the stakes of societal decisions would get that much higher too. Most externalized costs (the bad consequences of our actions that we can offload to others) would become deeply internalized given enough time. Politicians could no longer overlook the long-term consequences of their choices, as they’d live to witness them firsthand. Perhaps we’d be more incentivized to prevent radical climate change for the same reason. In this world, humanity becomes more thoughtful, because every action has enduring consequences that we can’t as easily hand off to future generations.

I think a lot about what a future with powerful AI systems might look like. We are building out new minds, and financial incentives have caused leading companies to do so at breakneck pace, so as to beat the others to the next most powerful model. In doing so, we’ve prioritized the advancement of capabilities over understanding. There are many risks involved with building a mind smarter than most or all humans. In a world in which all of us had more time, though, I wonder whether we could afford a different incentive structure, one in which we could stop and think more often.

Rethinking Life Trajectory

A friend of mine working on longevity told me her mom decided to go back to school in her sixties, out of faith that her daughter’s work would extend her life enough to justify that decision.

I see friends making life decisions predicated on their age, all the time.

Some examples:

- “I need to have kids by the time I’m 35”

- “My 20’s are for adventure”

- “College is the best four years of your life”

- “I’m too old for that”

Perhaps many of us would rethink our life trajectories in this world. Maybe a one-time, four-year university program would no longer be the end of our education. Maybe we’d go back to school periodically. Or perhaps we’d switch careers more often, or have children later in life, or wait longer to marry, or continue playing sports and pursuing hobbies as we age, to name a few examples. Or, if we weren’t limited to 30 or so “prime” years, perhaps we could afford to take more career risks – like producing art, or writing, or starting a company.

If you’re reading this, it’s hard to overstate what’s at stake for us. A video game where you can respawn is low stakes. In a life where you’ll most likely die before age 100, the stakes of dying prematurely are still capped. In a life that may last a very long time, death becomes more and more an unthinkable tragedy. That world is not all that distant.

If all of this makes you deeply uncomfortable, or if you disagree with the premise that we should live longer, I’d ask the following: if near the end of your life I asked you if you wanted one more day – one more day with your family, one more sunrise and one more sunset, one more favorite meal, would you say yes? And how about one more day after that? How far would this go?

What Then?

We are conceivably the first generation for whom reaching lifetime escape velocity is a real possibility. It would make sense to prepare, both individually and societally. Individually, this may mean taking better care of our physical health. Societally, I think we should direct more effort to a) preventative medicine, longevity, and cryopreservation and b) preventing outcomes that could derail these plans (e.g. deadly global pandemics, misaligned and powerful AI systems, climate change).

The egg we now carry in our hands holds within it the farthest reaches of the universe. Now, more than ever, we need to be careful not to break it.