The Murphy's Law Mindset

“We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars. Now we just look down, and worry about our place in the dirt.”

I just watched Interstellar for the second time in my life, 10 years after it first came out. Strange, because I’ve been telling people that it’s one of my favorite movies for over a decade now. In the meantime, I’ve managed to see Top Gun Maverick 7 times in theaters and Oppenheimer 5 times (yes, I’ve come to understand that I may have a condition).

Interstellar is a different kind of masterpiece, and it inspired this post.

Inevitability

There’s one core idea from the movie that lingers with me, and I don’t think it’s an obvious takeaway or the primary message Nolan intended. That idea is Murphy’s law. As the movie puts it, “anything that can happen will happen.” I first watched the movie when I was 13 years old, and this is one of the only lines I’ve remembered for all these years.

There is a related idea I’ve been contending with for some time now, amplified by the time I’ve spent working at Cradle and thinking about cryopreservation and longevity. The idea, put simply, is this:

We live in the first time ever in which it is conceivable that humans may transcend our biological lifespans.

How is this related? In Interstellar, the crew’s goal is to find a new planet suitable to life. There are multiple candidates, but there comes a point at which they have only enough resources to visit either Dr. Mann’s or Dr. Edmunds’ planet. This prompts an interesting argument from Dr. Brand: that life relies on lots of chance events, and that the proximity of Dr. Mann’s planet to Gargantua (a massive black hole) limits the odds of those chance events, thereby limiting the odds of finding life. This is because the black hole swallows things like asteroids and comets that, given enough time, might randomly lead to the right conditions for life.

Death is the black hole that swallows all of us. It is the only threshold we are certain to cross and the only one we cannot come back from. It also imposes hard limits on the range of events we might witness in our lifetimes. If you and I could live far beyond our normal biological lifespans, though, we greatly widen the scope of all possible things that we could experience (i.e. our personal light cones).

I’ve often come across the cultural meme that things are not possible, or the preference towards the underestimation of human potential. I get the sense that most people don’t think it is conceivable that one day humans will pilot spacecraft through man-made wormholes, or that we will slingshot around supermassive black holes, or that we might enter a black hole and communicate with past versions of ourselves. I think even fewer people would believe that one day they might do these things. Surely, we can’t take Murphy’s law at complete face value.

But the history of technology and indeed the history of life itself is a history of “Murphy’s law” moments. What we think is impossible pales in comparison to what we know has already happened. Humans once thought it impossible that we would one day join the birds in the sky, or that we would split the atom, or that we would send rockets into space and land them back on Earth, or that we would look, with our own eyes, at the tiny machinery of life that make us up. Today, many of us don’t yet believe that we will actually fuse two hydrogen atoms and achieve virtually boundless energy production.

We forget Murphy’s law. We forget that we are the ones who discovered fire, and built the wheel, and the steam engine, and the computer, and the airplane, and the rocket, and the microscope, and the ability to change DNA, to name but a few examples.

Zoom out. Consider that 13.7 billion years ago, a cosmic explosion hurled all matter and energy as we know it – including every atom in your body – outwards, randomly. Atoms found each other to make molecules, which found more molecules to form the compounds of life, which found other compounds to make cells; these cells obtained the will to survive and reproduce, and eventually form multicellular organisms, who then needed to find other multicellular organisms to mate with, and whose offspring needed to find their own mates to chuck the gene pool further into the future; and so on, until this process produced your parents, who had to find each other in a vast world of potential mates in order to produce you.

The improbable is more than just a stretch of the imagination. It is the very thread of your existence.

Five Dimensional Beings

One of the central plots of the movie is that there exist “supernatural” beings (referred to as “they”) communicating with Murph and Cooper from the future. These beings supposedly transcend the 4-dimensional world we live in (the three dimensions of space, plus time). For the majority of the movie it remains unclear who these beings are, why they care about Cooper, and how they are communicating with him.

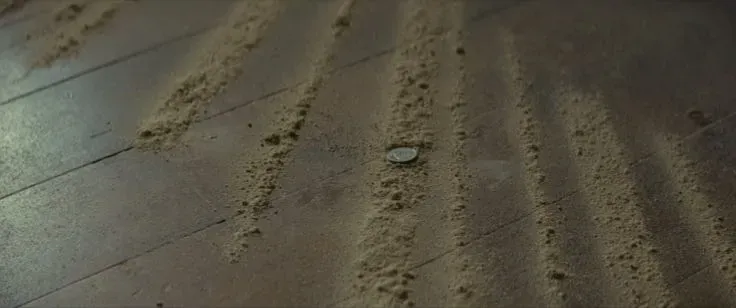

Throughout the plot, there are strange blips – “gravitational anomalies,” as the characters call them – like the binary code represented in the dust on Murph’s bedroom floor:

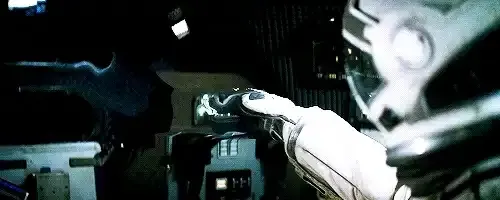

or the strange flashes of light that appear next to Dr. Brand in the spaceship.

At first, we don’t know what they are.

Near the end of the movie, though, Cooper enters the black hole and finds himself within a “tesseract” – a place where time is laid out in front of him as a physical space. He notices something: as he bangs on the virtual bookshelves in front of him, books fall and he glimpses into past versions of Murph’s bedroom. What he finds inside is himself, saying goodbye to Murph as he prepares to leave the house for NASA headquarters and begin the mission of finding humanity another home planet – the very mission that led him here, to this moment inside the black hole. Soon after, we see him navigate to the place in spacetime where we saw those strange flashes of light, and perform a “handshake” with a past Dr. Brand.

Thus we discover what the supernatural “they” was. It was Cooper. The tesseract was created not by aliens, but by humans who had evolved past the 4 dimensions of spacetime. The timeline was circular – Cooper from the future was trying to communicate with Cooper and Murph from the past.

The first time I watched Interstellar, these things seemed to me like fantastical and impractical visions of a future that would never come to pass. I don’t think that anymore. And while I’m not sure if or when we’ll become 5-dimensional beings and create tesseracts to communicate with past versions of ourselves, I am sure that many of the things that seem impossible today will soon become not only possible, but real.

I think we should plan for that future far more than we currently do.

What is Impossible?

We don’t have a very good track record of predicting the impossible. To illuminate this, here are a few examples of ideas and technologies that some of the greatest minds of their time thought impossible:

Copernicus’ heliocentric model (Martin Luther: “The fool wants to turn the whole art of astronomy upside-down. However, as Holy Scripture tells us, so did Joshua bid the sun to stand still and not the earth.”)

Heavier than air flight: (Lord Kelvin: “Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible.”)

Quantum physics (Albert Einstein: “God does not play dice with the universe”)

Fission power/atomic bombs (Ernest Rutherford: “Anyone who expects a source of power from the transformation of those atoms is talking moonshine.”)

I was curious and didn’t want to cherry pick my examples, so I tried to dig up some examples of things people thought impossible that have, so far, proven impossible:

-

Perpetual motion machines

-

Alchemy (turning base metals into gold)

-

Faster than light travel

-

Immortality

The common thread I find among this second list, with immortality being an exception, is that they violate our understanding of physics. Perpetual motion machines violate the conservation of energy; alchemy made the wrong fundamental assumption that there were only four elements that made up all matter (earth, water, air, and fire); faster than light travel is constrained by special relativity (Einstein’s relativity says that the energy required to accelerate an object at the speed of light is infinite).

Barring these known violations of physical laws, it seems to be the safer bet that when humanity envisions a future, it eventually comes to pass. What your parents called a magic trick you might explain with a simple equation or scientific insight.

As an aside, this is what makes biology so exciting to me – yes, it is the study of some of the most complex systems we know of, but so far we’ve found relatively few fundamental physical laws that would constrain us from solving its largest problems. Immortality (or at least serious life extension) falls under this category.

What is Possible?

I return to this image:

Contemplate the sheer scale and possibility of what exists beyond Earth. Black holes, stars many orders of magnitude the size of ours, other galaxies, habitable planets, life, other universes etc.

When things don’t violate physical laws, we should look at them as engineering problems and then apply Murphy’s Law thinking. If we can manage to avoid global catastrophic risks, i.e. great filters, I do believe humanity will walk on new planets, slingshot around black holes, and discover alien life forms (if they exist).

Some other futures I think will come to pass* (some obviously good, others more murky):

-

AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), then ASI (Artificial Superintelligence)

-

Automation of all menial labor

-

100% clean energy

-

Cryopreservation/life extension (like, serious life extension

-

Neurotechnologies for:

- Solving neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s, depression, and anxiety

- Forming deeper connections with other humans

- Understanding and altering emotions

- Improving cognition and memory

- Learning more effectively

- etc.

-

Augmented/Virtual reality indistinguishable from the real world (potentially through neurotechnologies)

*There are some big “ifs” here. Read the next section.

The Argument for Caution

I want to make a clarification. At this point, Marc Andreesen’s Techno-Optimist Manifesto may be ringing through your mind. I’m arguing that crazy new technologies that we think are impossible will become a reality. Surely that’s not a new point, so why am I writing this post?

I don’t want this writing to be misinterpreted as another version of the techno-optimist manifesto. I have a few strong disagreements with its framing. Namely, I don’t believe that we can just throw all caution to the wind and hope that a boundless acceleration towards futuristic technologies will lead us to utopia. But this mindset seems to pervade many fields right now, most notably AI. And that could be catastrophic.

In another post, I write about why the prospect of immortality or at least much longer lifespans makes the stakes of our decisions today much higher. In a nutshell, the argument goes like this: if there is a chance that we can live much longer lives – that we, and not just our distant descendants, can explore more of the world and the universe and hugely widen the scope of our life experiences – we have every obligation not to squander it. By “squander it”, I mean a couple of things: we could a) build new technologies so fast that we make fatal and irreversible mistakes, or b) we could slow down so much that we fail to address pressing problems (e.g. climate change). I’m sure there are more subtle ways we might mess up.

Imagine you’re standing on one side of a river. On the other side lies the elixir of life, all of the wealth and resources you’d need to live a happy and comfortable life, and more knowledge than currently exists in any library. I’ve given you and a small group of people one canoe so that you can cross – but the currents are strong and you’ll need to wait for them to die down.

Now, you’d be pretty upset if someone immediately stole the canoe, tried to cross, and got swept away along with your only means of crossing and winning the prize. Right? Likewise, you might take issue with somebody telling you to wait until the river stopped flowing.

Murphy’s law is double-edged, as we are always fighting against the universe’s tendency towards chaos. Steering society towards a future we want to live in will require caution and intentional, coordinated effort.

Conclusion

It is time we learn the lesson that the past has been trying to teach us. We should adopt a Murphy’s Law mindset towards the future. It need not be in some abstract way. When physics does not outlaw an outcome, and when humanity decides that outcome is important, real capital and real intellect flow towards manifesting it (this is what we call the “market”).

For the longest time, I did not fear death, because I saw it as natural. The same fate would come for all of us no matter what we did. But I did not think that some would dare to challenge that order. As a kid, I used to mix green and orange gatorade, call it immortality serum, and give it to my parents, because I’d promised them I’d find a way for them to live forever. 10-year-old Dhruv did not know that there was indeed a they from the future that would take this prospect seriously.

I believe that where we decide to explore, we will discover; where we find problems, we’ll solve them. On the flip side, I believe that where things can go wrong, they will. Our job, then, is to proceed with great effort and focus, but also caution and intentionality.

The takeaway I’m left with is this: if you believe in the kind of inevitability suggested by Murphy’s Law, you should allow yourself to entertain a future in which everything we do want comes to pass. And you should try like hell to make it that way.

There has never been a more critical time to do this.